Sampling is a design decision in distributed systems, but many teams still treat it as an implementation detail. Once the system drops telemetry, that visibility is gone permanently. No query, dashboard, or retrospective analysis can recover that data.

Sampling choices influence what engineers see during incidents, how much observable infrastructure costs to operate, and how much trust teams place in their data when systems behave unexpectedly.

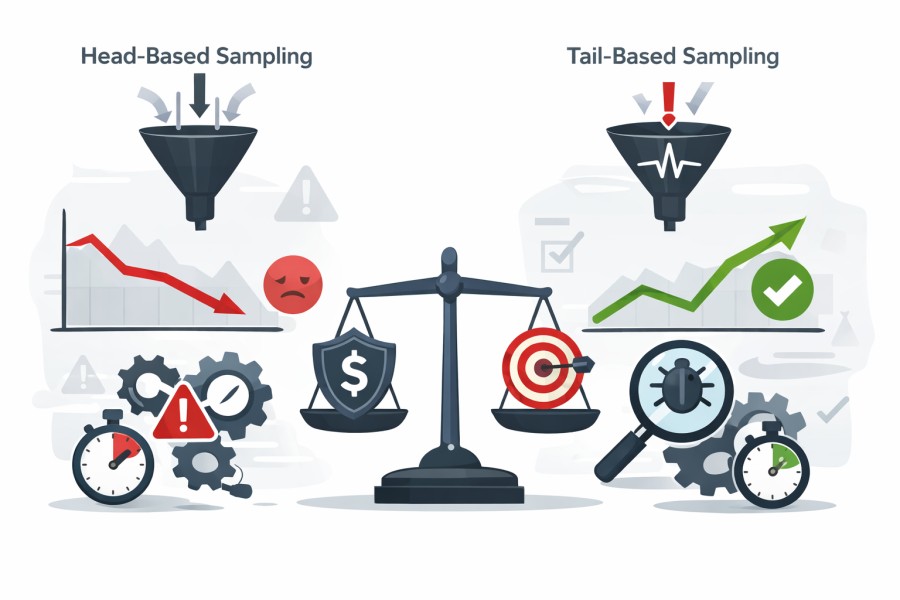

Head-based and tail-based sampling represent two fundamentally different approaches to managing telemetry volume. Their differences surface during traffic spikes, failure scenarios, and post-incident investigations, where trade-offs become impossible to ignore.

This article compares head-based vs tail-based sampling based on real operational behavior and how they shape observability.

This analysis is based on vendor documentation, production usage patterns, and real-world observability deployments across distributed systems.

Why Sampling Exists in Modern Distributed Systems

Modern distributed systems generate telemetry at a scale that did not exist a decade ago. Microservices, autoscaling, and high request concurrency multiply trace volume quickly. A single user request can fan out across dozens of services. Each service emits spans, logs, and metrics. At scale, this results in millions of traces per minute.

Tracing every request is rarely sustainable. Full tracing increases network traffic, storage usage, and query cost. It also adds runtime overhead to applications and collectors. As traffic grows, these costs grow linearly or worse. Most teams eventually reach a point where retaining all traces degrades system performance or becomes financially impractical.

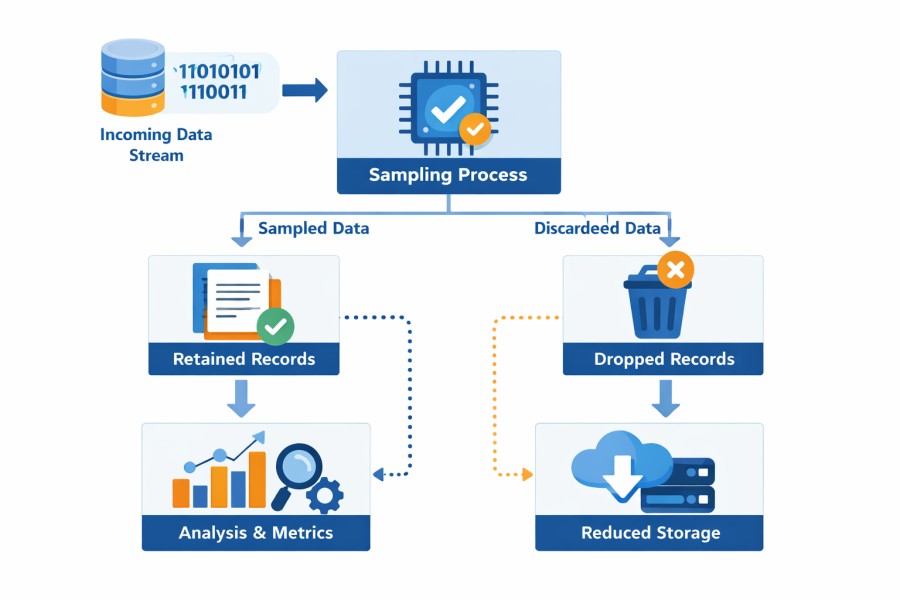

Sampling exists to manage this pressure. It is a controlled reduction of telemetry volume, designed to preserve useful signals while keeping cost and system load within acceptable limits. Every observability platform samples data in some form. The difference is not whether sampling happens, but how it is applied.

Where Sampling Decisions Live in Modern Observability Stacks

Sampling strategy is often discussed as a conceptual choice, head-based versus tail-based. But where the sampling decision is enforced has a far greater impact on observability outcomes than most teams realize. In modern observability stacks, sampling decisions typically occur at one of three layers:

- SDK-level sampling happens inside the application instrumentation. Decisions are made at the very start of a request, before latency, errors, or downstream behavior are known. While this approach is lightweight and predictable, it permanently discards context early. Once a trace is dropped at the SDK, no downstream system can recover it.

- Collector-level sampling evaluates traces after spans are emitted, often using buffering and aggregation. This allows decisions based on latency or error signals, but introduces operational risk. Collectors must hold spans in memory until requests complete, which can create backpressure or data loss during traffic spikes.

- Backend-level sampling occurs after telemetry leaves the customer’s environment. These decisions are opaque, vendor-controlled, and often irreversible. Teams rarely know which traces were dropped or why, which can complicate debugging, auditing, and governance.

Each layer changes what data is available later. Early decisions reduce load quickly but remove context. Late decisions preserve context but require more resources. This is why “sampling rate” is not reliable. A percentage does not explain what is lost, when it is lost, or why. The critical factor is timing. Whether a trace is sampled before it runs or after it completes changes data quality, operational risk, and cost behavior. This timing difference is the foundation of head-based and tail-based sampling.

The practical implication is that sampling strategy cannot be evaluated independently of the enforcement location. Two teams using tail-based sampling may experience different outcomes depending on whether sampling occurs in SDKs, collectors, or proprietary backends. This distinction is rarely made clear, but it determines how much context survives when systems are under stress.

How OpenTelemetry Shapes Head-Based and Tail-Based Sampling

OpenTelemetry standardizes how telemetry is generated and transported, but it does not change the underlying constraints of distributed systems. Volume, cost, and performance limits still apply. What OpenTelemetry changes is where sampling decisions can be made and how consistently those decisions can be enforced.

In OpenTelemetry, sampling typically occurs at two layers:

- At the SDK level, where head-based sampling decisions are made when a trace starts

- At the collector level, where tail-based sampling decisions can be made after a trace completes

Head-based sampling in SDKs keeps overhead low. It avoids buffering and minimizes runtime cost. Once a trace is dropped, no downstream system can recover it. This works well for high-throughput services, but it carries the same visibility limits as traditional head-based sampling.

Tail-based sampling becomes possible through OpenTelemetry collectors. Collectors can observe complete traces before making a decision. This allows sampling rules based on:

- Error status

- Latency thresholds

- Service or attribute context

OpenTelemetry made this approach more accessible by standardizing trace context, span relationships, and collector pipelines. Without this consistency, tail-based sampling is difficult to implement at scale. However, OTel does not eliminate sampling trade-offs. Collector-based sampling still requires buffering, memory, and careful backpressure handling. Under load or partial failure, traces can still be dropped or arrive incomplete.

This is why sampling strategy still matters in OTel-native stacks. Where sampling happens, and when the decision is made, still determines cost behavior, system stability, and the quality of observability data.

Head-Based Sampling: What You Gain and What You Lose

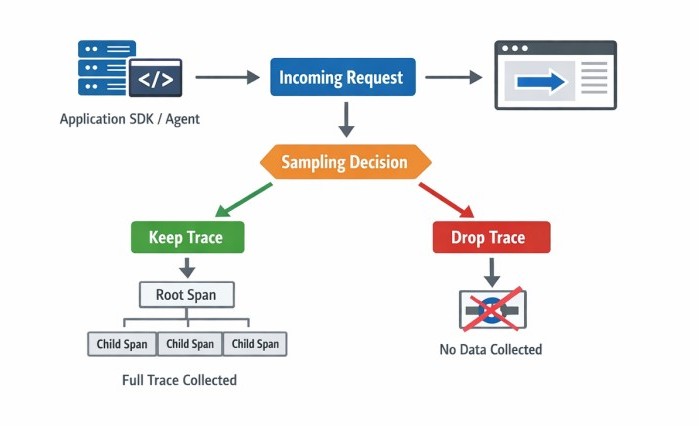

Head-based sampling is a tracing approach where the decision to keep or drop a trace is made when the request starts, also known as the root span. The choice happens before the system knows how the request will behave. Once the decision is made, it propagates downstream through the entire trace context, which includes critical information, such as trace and span IDs. If a trace is dropped at the start, no downstream span is collected.

Furthermore, head-based sampling is implemented in application SDKs or agents. The sampler evaluates simple inputs such as a fixed probability, request attributes, or trace flags. Because the decision is made early, the system avoids buffering and additional processing. This keeps runtime overhead low and predictable.

For example, Consistent Probability Sampling or Deterministic Sampling is the most common type of head-based sampling. It makes sampling decisions based on a specific trace percentage (say 5%) to sample and the trace ID. It makes sure to sample the whole traces without missing any spans.

Strengths

In head-based sampling, all spans from a request follow the same sampling decision. This is the biggest advantage of this type of sampling and allows customers to get end-to-end traces. Strengths of head-based sampling:

- Cost-efficient: Head-based sampling helps reduce the overall observability cost, egress costs in particular. Since it makes the sampling decisions at the start and collects and transmits only a subset of traces, minimum data leaves the system. This reduces data storage and networking costs.

- Complete traces: Once head-based sampling has selected a trace, it collects and retains its spans. This allows you to view the traces completely and analyze the journey of a request in a system.

- Easy to deploy: Head-based sampling is easy to implement with minimal infrastructure. It also integrates easily with your existing systems without additional infrastructure or storage. So, the operation overhead is lower.

These properties make head-based sampling well-suited for large, steady workloads where cost control and system stability are primary concerns.

Limitations

Head-based sampling has structural constraints. The decision is made without the full request context. Latency, errors, and downstream behavior are not known at trace start. As a result:

- Critical traces are dropped

- Late-stage or rare failures can be missed

- Error-heavy traces may be underrepresented

These losses are not random. They are a direct consequence of deciding before outcomes are known. Head-based sampling reduces volume effectively, but it does so by accepting blind spots in exchange for simplicity and predictability.

Tail-Based Sampling: Visibility With a Cost

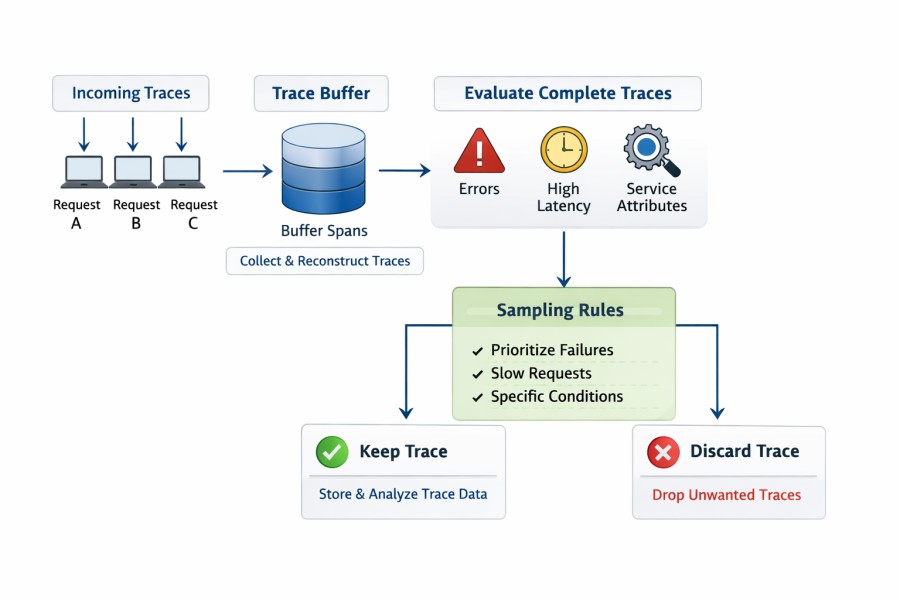

Tail-based sampling is a tracing approach where the decision to keep or drop a trace is made after the request has completed. The system observes the full execution path before deciding. This allows sampling decisions to be based on outcomes rather than probability. Traces are evaluated using signals such as errors, latency, and service attributes.

Moreover, tail-based sampling is implemented at the collector layer. Spans are temporarily buffered while the collector reconstructs complete traces. Once the trace is complete, sampling rules are applied. These rules can prioritize failed requests, slow paths, or traces that match specific conditions. Traces that do not meet the criteria are discarded after evaluation.

Strengths

Tail-based sampling optimizes for visibility and accuracy:

- Full request context is available before decisions are made

- Errors and high-latency traces are more consistently retained

- Rare and intermittent failures are less likely to be missed

This improves confidence during debugging and incident analysis. When failures occur infrequently or late in execution, tail-based sampling preserves the traces that matter most.

Limitations

Tail-based sampling introduces operational and cost challenges:

- Traces are not complete: Tail-based sampling may produce incomplete traces. It requires storing all the spans of a trace temporarily in the same location. Managing this is complex and costly in distributed systems.

- Additional infrastructure: To store and process spans and make a sampling decision, tail-based sampling needs additional infrastructure. This increases complexity, cost, and operational burden.

- Memory pressure increases during traffic spikes

- Collectors require careful tuning to avoid backpressure

Also, during incidents, when traffic and errors spike at the same time, tail-based sampling can cause sudden increases in resource usage. This can lead to cost spikes, partial trace loss, or dropped data if limits are exceeded.

Tail-based sampling improves signal quality, but it does so by shifting cost and complexity from ingestion to processing. These trade-offs become more visible as systems scale or enter failure states.

Head-Based vs Tail-Based Sampling: The Differences That Actually Matter

| Dimension | Head-Based Sampling | Tail-Based Sampling |

| Decision timing | Made at the request start using limited context (attributes, probability) | Made after trace completion using full context (latency, errors, span relationships) |

| Information available | Partial context only | Full execution outcome and trace structure |

| Signal quality | Can miss failures, slow paths, and rare anomalies | Retains outcome-driven signals (errors, latency, anomalies) |

| Volume control | Predictable and capped at ingestion | Unbounded at ingestion, filtered only after processing |

| Cost behavior (steady state) | Stable, predictable ingestion and storage costs | Higher processing and buffering costs even during normal operation |

| Cost behavior (incidents) | Cost remains relatively stable | Cost pressure spikes as more anomalous traces are retained |

| Infrastructure overhead | Low (no buffering, no state management) | High (buffering, state, trace assembly, coordination) |

| Failure modes under load | Missing classes of traces without visibility | Memory pressure, backpressure, dropped spans, collector scaling complexity |

| Scalability model | Simple horizontal scaling | Complex scaling due to trace affinity and state requirements |

| Debugging reliability | Lower confidence during rare or late-stage failures | Higher confidence due to outcome-based retention |

| MTTR impact | Risk of missing critical evidence | Better incident diagnosis and faster resolution |

| Risk trade-off | Predictable cost and stability, but blind spots | Better diagnostics, but higher operational and cost risk |

Context vs predictability

Head-based sampling makes the decision to keep or drop a trace at the start of the request. It uses limited information available at entry (such as attributes or fixed probabilities). This early decision reduces runtime overhead and keeps ingestion rates stable because decisions do not depend on trace outcomes.

Tail-based sampling delays the decision until after the trace completes, using full context such as final latency, error status, and span relationships. This allows outcome-driven selection of important traces for retention. OpenTelemetry sampling documentation emphasizes that head-based decisions cannot reliably capture failures or slow traces because the sampler lacks complete information at trace start, and the full outcome is not yet visible.

So, head-based sampling thus favors predictability in volume and cost. Tail-based sampling favors contextual accuracy, especially for capturing anomalous behavior that only becomes visible after execution.

Cost behavior during steady state vs incidents

In steady state operations, head-based sampling acts like a fixed throttle. If you sample 10 %, you roughly cap trace volume early, which stabilizes storage and processing costs. Many observability platforms default to this behavior because it gives a predictable downstream load without buffering or re-evaluation.

Tail-based sampling does not cap volume at the start. All spans must be received and assembled before evaluation, which increases processing and buffering costs even during normal operation. During incidents, tail-based sampling tends to retain a higher proportion of traces because error and latency signals are used to decide retention. This concentrates cost pressure at the same time, and the system may already be stressed.

These operational cost pressures matter because downtime is expensive for businesses. A recent industry overview found that unplanned downtime can cost large organizations on average $9,000 per minute (~$540,000 per hour).

Failure modes under load

With head-based sampling, the system does not need span buffering or state, so under load, the sampling system itself does not typically become a bottleneck. Instead, the risk is that whole classes of traces (especially rare or slow ones) are simply not collected. Teams may not notice missing signals until a problem recurs.

Tail-based sampling requires buffering and a state in the collector to assemble complete traces before applying rules. Under high load, this can lead to memory pressure, backpressure, or dropped spans before a trace completes. OTel Collector documentation warns that tail sampling must ensure all spans for a trace are received by the same instance to make correct decisions, which complicates scaling in microservices environments.

Impact on debugging confidence and MTTR

MTTR (mean time to resolution) depends on whether the traces you need exist when problems occur. Head-based sampling can miss low-frequency failures or late-stage slowdowns because the decision was made before those signals occurred. This can leave engineering teams without the evidence they need to diagnose problems confidently.

Tail-based sampling improves the chances of retaining traces that reflect actual errors and high latency because decisions are based on outcome signals. This generally improves confidence in debugging and incident analysis.

The choice between these strategies is not about one being universally better. It is about which risk you choose. Head-based sampling prioritizes stability and predictable cost but accepts blind spots. Tail-based sampling prioritizes diagnostic completeness but incurs higher operational overhead and cost pressure, particularly during incidents.

Head vs Tail Sampling in Practice: A Production Incident Scenario

Consider a distributed system processing 30,000 requests per second across multiple services. Under normal conditions, both head-based and tail-based sampling appear to work acceptably. Latency is low, error rates are stable, and dashboards look clean.

Now introduce a partial outage.

A downstream database begins responding slowly, pushing p95 latency from 120 ms to over 900 ms for a subset of requests. Error rates increase from 0.1% to 2%, but only for specific service paths.

- With head-based sampling, many of these slow and failing requests are dropped before latency and error signals are known. Engineers investigating the incident see incomplete traces, missing spans, and fragmented request paths. Root cause analysis depends on guesswork and correlation across metrics rather than trace evidence.

- With tail-based sampling, slow and failing requests are retained because decisions are made after requests complete. Engineers can see full execution paths, identify where time was spent, and trace how failures propagated across services.

However, this visibility comes with trade-offs. During the same incident, buffering pressure increases sharply. If collectors are under-provisioned, spans may be dropped due to memory limits or backpressure, creating a different class of blind spots.

The takeaway is not that one approach “wins,” but that sampling behavior changes under incident conditions, and those changes directly affect Mean Time to Resolution. Sampling strategy determines which failures are visible when teams need answers most.

Head-Based vs Tail-Based Sampling: Cost and Scale Implications

Ingestion and Storage Cost

Sampling controls how much trace data enters and stays in your system. Head-based sampling drops traces early in the SDK/agent, reducing network traffic, collector load, and storage writes before they occur. This makes ingestion volume easier to forecast as traffic grows because you know up front roughly what percentage of traces you will keep.

In contrast, tail-based sampling must ingest all spans first so it can evaluate the full trace context before keeping or dropping it. Even traces that are eventually discarded still consume bandwidth, collector CPU, and memory. This means ingestion and processing costs scale closer to unsampled traffic volume, even if fewer traces are stored long-term. Sampling at the tail trades early cost reduction for later selective retention.

To put scale in perspective, one observability vendor’s internal analysis shows that raw trace volume generated by applications can be approximately five times the volume of logs ingested, and even sampled traces (after head sampling) can be around twice the volume of logs stored. This highlights how large trace workloads can become relative to other telemetry if not controlled early.

Why tail-based sampling costs often spike during incidents

Incidents change the shape of incoming traces. Error rates rise, latency increases, and retries multiply. Tail-based sampling rules are often designed to retain traces that show errors, high latency, or unusual behavior. During an incident, these rules cause more traces to be kept and forwarded for storage and analysis.

This creates a resource surge precisely when the system is already stressed:

- Collectors need more memory to buffer spans

- CPU usage increases for evaluation

- Ingestion pipelines see more traffic

- Storage and query costs rise due to a higher retained trace volume

Because tail sampling delays the decision until after trace completion, you incur higher processing and memory costs during incidents, making cost behavior less predictable compared to head sampling.

Predictability vs Accuracy Trade-Offs

The fundamental trade-off between sampling strategies is predictability versus accuracy. Head-based sampling favors predictability:

- Ingest and storage costs can be modeled based on a fixed rate

- Operational impact on collectors and SDKs remains stable

- Capacity planning is straightforward

The downside is lowered accuracy for rare or complex events. Head sampling may miss traces that only appear interesting after execution. Tail-based sampling favors accuracy:

- Decisions are based on complete trace outcomes

- Error traces and slow paths are more likely to be retained

- Diagnostic depth improves during investigations

The downside is less predictable costs and resource use. In large systems, buffering and evaluating every trace before sampling increases load even if long-term retention is less. The result is a more complex cost surface that varies with traffic shape and incident patterns.

Head-Based vs Tail-Based Sampling: Operational & Governance Considerations

Operational Ownership of Sampling Pipelines

Sampling creates an operational surface that must be owned. With head-based sampling, ownership usually sits with application teams. Logic lives in SDKs or agents. Changes require redeployments, but runtime behavior is simple and predictable.

Tail-based sampling shifts ownership to platform or observability teams. Sampling logic moves into shared collectors and pipelines. These components must be deployed, scaled, monitored, and tuned. A single change can affect many services at once. This increases coordination overhead and raises the bar for operational maturity.

At scale, unclear ownership is a risk. When sampling behavior changes unexpectedly, teams need to know who controls it and who is responsible when visibility is lost.

Backpressure, Failure Domains, and Recovery Risk

Head-based sampling introduces minimal backpressure risk. Data is dropped before it enters the pipeline. Under load, the system sheds volume quietly. Failures are local to the emitting service.

Tail-based sampling introduces shared failure domains. Collectors buffer spans, assemble traces, and apply rules. Under load or partial outages:

- Buffers can fill

- Memory pressure increases

- Backpressure propagates upstream

- Spans or partial traces may be dropped

Recovery also differs. Head-based sampling drops data cleanly. Tail-based sampling can fail mid-assembly, leaving gaps that complicate post-incident analysis.

Governance Implications

Sampling decisions define what operational evidence exists.

Who Decides What Gets Dropped

Head-based sampling often uses fixed rates or simple rules. Data is dropped implicitly, before outcomes are known. Governance is indirect and rarely revisited.

Tail-based sampling uses explicit, policy-driven rules. This raises ownership questions. Who defines these rules? Platform teams, application teams, or security teams? Without clarity, policies can drift away from business and compliance needs.

Auditability of Discarded Data

Auditability becomes harder as sampling grows more complex. Head-based sampling is simple but opaque. Dropped data leaves little record. Tail-based sampling can be auditable, but only if rules, decisions, and changes are tracked.

In regulated environments, this matters. If traces support incident reviews or audits, teams must explain why certain data exists and why other data does not. Sampling improves observability, but without auditability, it can undermine trust.

Hybrid and Adaptive Sampling: Why Most Teams Don’t Choose One Strategy

Why Pure Head-Based or Tail-Based Sampling Rarely Survives Scale

Pure sampling strategies work at a small scale, but their limits surface quickly as systems grow. Head-based sampling offers predictable cost and low overhead, but it consistently underrepresents rare failures, long-tail latency, and complex request paths. Teams often respond by raising sampling rates, which reduces blind spots but erodes cost control.

Pure tail-based sampling fails differently. Buffering, state, and evaluation overhead increase with traffic. During bursts or incidents, collectors become stressed and costs become volatile. Because sampling infrastructure is shared, failures affect many services at once. At scale, most teams find that neither approach remains acceptable on its own.

Emergence of Hybrid and Adaptive Approaches

Hybrid sampling combines early and late decisions. Some traces are sampled early to cap volume. Others are evaluated later to retain high-value signals such as errors or slow paths. This balances baseline cost control with diagnostic depth.

Adaptive sampling extends this model by changing behavior based on conditions. Sampling rates may decrease during healthy periods and increase during failures. This allows teams to preserve important data when it matters most, without permanently raising cost. These approaches emerge from operational pressure, not theoretical design.

When Teams Are Forced to Revisit the Sampling Strategy

Sampling strategies are rarely revisited proactively. They are revisited when something breaks.

Common triggers include:

- Incidents where critical traces are missing

- Cost spikes tied to traffic growth or failures

- New services with different reliability or compliance needs

- Platform changes, such as OpenTelemetry adoption

At this point, teams are no longer choosing between strategies in theory. They are responding to real failures in visibility, cost, or stability. Hybrid and adaptive sampling becomes a response to scale, not a preference.

Some teams choose to implement these hybrid and adaptive approaches through self-hosted or BYOC observability platforms that keep sampling logic inside their own environment.

How CubeAPM Approaches Sampling

CubeAPM uses Smart Sampling to avoid the trade-offs teams face with traditional head-based and tail-based sampling. Instead of making a single, fixed decision, sampling is treated as an adaptive control mechanism that responds to how systems behave in production.

Key aspects of CubeAPM Smart Sampling:

- Context-aware sampling: Decisions are influenced by real runtime behavior, such as latency shifts, error patterns, and unexpected execution paths, rather than a static percentage applied at trace start.

- Drops routine traffic: Healthy, repetitive requests are dropped to reduce noise and storage overhead. It keeps costs predictable during steady-state operations.

- Preserves anomalous behavior automatically: When errors spike or latency deviates from normal baselines, Smart Sampling increases retention so engineers have the context needed during incidents.

- No full-trace buffering: Unlike pure tail-based sampling, Smart Sampling does not require holding all spans in memory until a trace completes, reducing operational complexity and resource pressure.

- Sampling decisions stay inside your environment: With self-hosted and BYOC deployments, sampling logic runs within the customer’s infrastructure, allowing teams to audit, tune, and align behavior with their own systems rather than vendor-imposed rules.

- Easier to scale: Smart Sampling balances signal quality and cost stability, hence, scalable. It avoids the blind spots of head-based sampling and the volatility of tail-based systems.

Head-based vs Tail-based vs Smart Sampling

| Aspect | Head-based sampling | Tail-based sampling | CubeAPM Smart Sampling |

| Decision timing | At the request start | After trace completion | Adaptive, based on runtime behavior |

| Context awareness | Limited | Full | High, without full buffering |

| Incident visibility | Often misses rare failures | Fully self-hosted / BYOC | Strong and immediate |

| Operational overhead | Low | High (buffers, memory) | Moderate, controlled |

| Cost predictability | High | Variable during spikes | Predictable with signal retention |

| Control & auditability | Limited | Limited in SaaS | Fully self-hosted/BYOC |

Choosing the Right Sampling Strategy Based on System Reality

High-Throughput Systems

High-throughput systems are constrained by volume first. Request rates are high, traffic is bursty, and small inefficiencies multiply quickly. In these environments, head-based sampling is often the baseline because it drops data early and keeps overhead predictable. Ingestion volume scales in a controlled way, which simplifies capacity planning and protects system stability.

Tail-based sampling can still be useful, but only in narrow scopes. Buffering and trace assembly scale with raw traffic, not retained data. At very high throughput, this increases memory pressure and shared failure risk in collectors. As a result, many teams reserve tail-based sampling for critical services or known failure paths rather than applying it broadly.

Incident-Prone Environments

Incident-prone systems fail in ways that are hard to predict. Errors are intermittent. Latency spikes late in request lifecycles. In these conditions, head-based sampling often misses the traces that matter most because decisions are made without outcome context.

Tail-based sampling becomes more valuable because it evaluates completed traces. Error-heavy and slow paths are more likely to be retained, which improves debugging confidence and shortens investigations. The trade-off is volatility. During incidents, resource usage and cost increase at the same time the system is under stress, and teams must plan for that explicitly.

Cost-Sensitive Platforms

Cost-sensitive platforms optimize for predictability. Budgets are fixed, and growth is planned. Head-based sampling aligns well with these constraints because cost scales in a stable and explainable way. Sampling rates can be adjusted gradually without sudden spikes in ingestion or storage.

Tail-based sampling complicates cost control. All traces must be ingested and evaluated before being dropped. During failures or traffic spikes, more traces are retained by design. This makes costs harder to forecast and harder to justify. When used in cost-sensitive environments, tail-based sampling is usually tightly scoped or time-bound.

Regulated or Audited Systems

Regulated systems must explain not only what data exists, but why other data does not. Sampling becomes a governance decision with audit implications. Head-based sampling is simple but opaque. Data is dropped early, and justification is often limited to configuration defaults.

Tail-based sampling allows explicit, policy-driven decisions, but only if those decisions are logged and traceable. Without audit trails, increased visibility does not translate into defensible governance. In regulated environments, teams prioritize clear ownership, documented policies, and explainable behavior over maximum data retention. Sampling strategy is chosen based on what can be defended later, not just what helps debugging today.

Final Takeaway: Sampling Shapes What You Can Know

Sampling defines the limits of observability. Once data is dropped, it cannot be recovered. This means sampling decisions directly determine which failures are visible and which are never seen. Poor choices create blind spots that surface during incidents, when missing context slows diagnosis and reduces confidence.

The right strategy balances visibility, cost, and operational reality. There is no universal answer. Systems differ in scale, failure patterns, budgets, and governance needs. Teams that treat sampling as an intentional architectural decision and revisit it as systems evolve avoid learning these trade-offs during outages.

If you want to design a sampling strategy that fits your system reality, start by auditing where sampling decisions are made today, what data is being dropped, and why. The gaps you find there usually explain your biggest observability blind spots.

Disclaimer: The information in this article reflects the latest details available at the time of publication and may change as technologies and products evolve.

FAQs

1. Is tail-based sampling always better than head-based?

No. Tail-based sampling preserves high-value signals like errors and slow traces, but adds buffering and operational complexity. Head-based sampling is simpler and more predictable. The right choice depends on which trade-offs a system can tolerate.

2. Where should sampling decisions be enforced: SDKs or collectors?

SDK-level sampling reduces downstream load but permanently drops context. Collector-level sampling makes better-informed decisions but shifts cost and risk to the collector. Most mature setups use a combination of both.

3. How does OpenTelemetry change sampling choices?

OpenTelemetry makes sampling an explicit design decision rather than a hidden vendor default. It allows teams to move sampling logic between SDKs and collectors, increasing flexibility and responsibility at the same time.

4. What happens to sampling during traffic spikes?

Head-based sampling remains stable because decisions are made early. Tail-based sampling must buffer more data, which can increase memory pressure and lead to dropped or partial traces if limits are exceeded.

5. Why do teams change sampling strategies as they scale?

Early systems favor simplicity and cost control. As scale and incident complexity grow, the cost of missing critical traces increases, pushing teams toward tail-based or hybrid approaches.