Software downtime not only degrades trust but also carries a high financial burden for enterprises. If we go down memory lane, the financial cost is hard to ignore. In 2019, a 14-hour outage cost Facebook an estimated $90 million, and a 5-hour outage in 2021 cost the company $100 million. In this environment, observability platforms are no longer passive dashboards. They are part of the system’s reliability posture.

System failure is no longer an isolated issue. Systems are more interconnected, and companies are fully embracing microservices architecture and distributed systems. Teams typically become acutely aware of this during high-traffic incidents, when observability systems are under the same stress as the applications they are meant to monitor. With this in mind, redundancy and high availability of observability systems are critical.

In this piece, we take an in-depth look at how modern observability systems handle failure and how redundancy and availability are achieved. Understanding these internal failure handling and redundancy strategies is key to evaluating whether an observability platform is trustworthy when systems are at their weakest.

Why Failure Handling Matters in Observability Systems

Failure handling matters in observability because incidents change system behavior instantly. It is critical because when applications break, observability systems remain functional and resilient. When a software outage is reported, the observability system remains as a resilient and active partner that will help teams resolve the issue.

Here is why handling failure is critical in modern observability:

Prevents Data Loss

The inability of an observability tool to handle system failure properly results in data loss. For instance, a spike in traffic might cause the telemetry pipeline to crash, losing visibility when it is needed the most. Robust failure handling guarantees:

- Persistent data handling: Prevents loss of telemetry data when there is a surge in traffic. Observability systems use ques to manage data when traffic spikes.

- Reliable Alerts: Ensures that alerts are still delivered, even when the monitoring system is experiencing significant stress.

Guarantees Swift Root Cause Analysis

Failure in distributed systems can escalate quickly. A resilient observability platform that handles failure has a myriad of benefits, including:

- Identifying issues: Critical in distributed systems, as it identifies the components in a microservice affecting the whole application.

- Correlating data: Connect logs, traces, and metrics to identify the root cause.

Prevents Observability Blind Spots

When a monitoring system breaks during an incident, everything slows down. Engineers stop looking at the application and start questioning the tools that are supposed to help them. Dashboards freeze, queries time out, and suddenly, the team is troubleshooting the monitoring platform instead of the outage itself. Teams usually become aware of this failure mode during peak incidents, when observability systems are under the same load and pressure as the applications they are meant to monitor.

Failure handling keeps the observability infrastructure, preserving access to the telemetry data pipeline.

Making Partial Failures Manageable, Not Chaotic

When systems start to fail, they rarely go down all at once. More often, certain paths slow down, specific features break, or a subset of users feel the impact first. In those moments, teams need clarity, not assumptions.

What Failure Means in Observability

Failure in observability is not often a pure outage in which everything ceases to function. In most cases, it manifests itself in the form of missing data, delayed alerts, sluggish queries, or partial visibility at the time when the engineers most require it. The fact that these failures are subtle is dangerous. Dashboards may load, and charts may render, yet critical signals are delayed or missing, creating a false sense of confidence.

To understand where observability really breaks under pressure, it helps to look at failure through a layered approach. Most issues surface in three places: how data is ingested, how it is stored and queried, and how control systems behave compared to the actual data flowing through the platform.

Data Ingestion Failures

Data ingestion failures are a critical concern in observability because problems at this initial stage ripple through everything that follows. When telemetry does not enter the system correctly, dashboards become misleading, alerts lose accuracy, and engineers begin to question the reliability of the data itself. In many incidents, ingestion failures are the earliest signal that the observability system is under stress.

This typically surfaces during traffic spikes or cascading failures, when telemetry volume increases sharply at the same time teams most rely on timely signals.

Failures during the data ingestion process commonly fall into a few recurring categories, each with different causes and consequences.

- Telemetry drops: Occur when agents cannot export data or collectors are overwhelmed by sudden spikes in volume. Common causes include CPU saturation on collectors, network throttling, and unbounded retry queues.

- Backpressure: Built when the downstream components (processors or storage layers) become slower.

- Network partitions: This happens when agents, collectors and ingestion endpoints lose contact

Storage & Query Failures

Observability is based upon telemetry information in the form of logs, metrics, and traces to assist engineers determine what occurs within a system. In an actual sense, observability does not experience a failure blast when the storage or query paths become unresponsive. Rather, it is made sluggish, incomplete, or deceitful. These failures often surface during incidents, when data volume and query pressure increase at the same time.

Teams often encounter these issues during major incidents, when data volume and query concurrency rise simultaneously, exposing contention and latency that are not visible in steady-state operation.

Common storage and query failures tend to fall into a few predictable patterns.

- Hot path overload: This happens when a small subset of telemetry dominates reads or writes. A single service, or endpoint, can generate huge traffic, putting pressure on specific storage or query paths even when total capacity looks fine.

- Index corruption or lag: May happen when imposed on overload.

- Slow queries during incidents: During major incidents, query concurrency often increases substantially, and median query latency can grow by 300% or more.

Control Plane vs Data Plane Failures

Control plane and data plane are challenging failures since the system might appear functional on the surface. Control plane handles configurations, dashboards, and alert definitions, whereas the data plane handles real-time ingestion and telemetry processing.

- Why dashboards may load but data is missing: Dashboards load because the control plane is available, even though the data plane is failing to ingest or process fresh telemetry.

This is rarely obvious during normal operation and is usually identified only after post-incident analysis reveals that fresh telemetry was delayed, incomplete, or never processed.

- Why alerts fire late or not at all: Alerts fire late or fail because delayed or incomplete data from the data plane prevents timely alert evaluation.

What We’ve Seen Go Wrong During Real Incidents

On paper, observability systems look resilient. In real-world scenarios when incidents occur, unreliable observability platforms are the first thing to break. When telemetry volume spikes and systems are under stress, weaknesses in observability architecture surface quickly. These failures usually appear when observability is treated as a collection of tools rather than a system that must remain reliable during failure.

These patterns tend to emerge when observability is treated as a collection of tools rather than a system that must remain reliable under failure conditions.

- Observability systems failing prior to the application: Telemetry pipelines are often more susceptible to traffic spikes than the applications they monitor. Because a single user request can generate dozens of logs and traces, the observability infrastructure can reach saturation and fail while the primary application is still functioning, leaving operators ‘blind’ during a critical window.

- Alerts delayed due to overloaded pipelines: Queues in ingestion and processors cause delays in evaluating the alerts by several minutes, or no alert is generated at all. This makes observability a post-incident reporting mechanism rather than a pre-incident warning mechanism.

- Partial visibility causing wrong incident conclusions: This is because when only a portion of the system can be observed, engineers fix what they can see and not what is actually malfunctioning causing time wastage and recurrence of incidents.

- “Green dashboards” while users are impacted: Dashboards appear healthy because control planes and cached data remain available.

Redundancy in Observability Platforms: What It Really Means

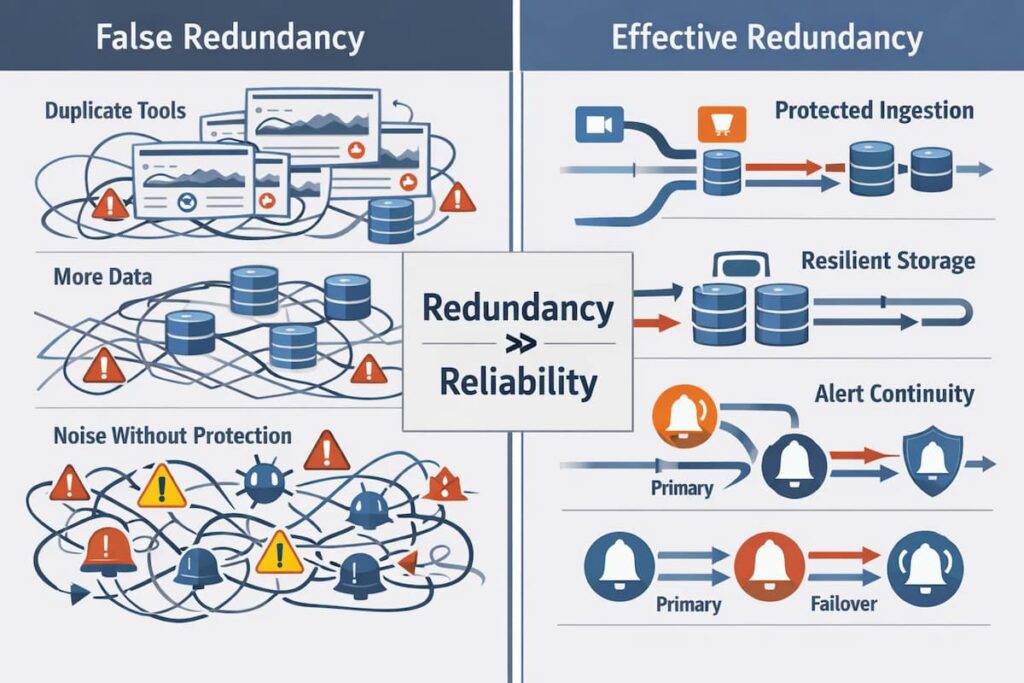

Redundancy in observability is often misunderstood. Many teams assume that more tools, more data, or duplicate dashboards automatically mean higher reliability. In practice, this kind of overlap increases cost and noise without protecting observability during real failures.

Teams often discover this during multi-region or high-traffic incidents, when redundant systems remain online but still deliver delayed or incomplete observability data.

Effective redundancy is intentional. It is designed to keep critical observability paths available when parts of the system fail. True redundancy is not about duplication for safety’s sake. It is about placing resilience where failures are most likely to occur.

To understand the significance of redundancy, it is essential to look at its practicality in observability

Ingestion-level Redundancy

Ingestion is the first failure point under load.

- Multiple collectors: Distributing ingestion across collectors prevents a single failure or overload from stopping telemetry flow.

- Buffering and retries: Short-term buffering and bounded retries absorb spikes and transient failures without overwhelming downstream systems.

Storage-level Redundancy

In this category, the redundancy ensures data durability at the expense of cost.

- Replication strategies: Replication of data between nodes or regions minimizes the loss of data in case of failure.

- Trade-offs between durability and cost: Increased replication enhances resiliency, although it raises the cost of storage and write amplification.

Query-path Redundancy

Query redundancy fails to get rid of contention. Instead, they keep investigation paths available during incident occurrence.

- Load balancing: The reason is the queries are distributed among the nodes, meaning that no single query engine will be a bottleneck.

- Read replicas: Replicas remove investigation queries along with ingestion and indexing queries.

- Why redundancy doesn’t guarantee speed: Redundancy enhances availability, and the high query volumes during incidents may still reduce response time.

High Availability vs High Cost: The Hidden Trade-off

High availability in observability sounds simple: more replicas, more redundancy, and always-on dashboards. In reality, it comes at a cost that isn’t always obvious. Every layer of HA, from ingestion to storage to query paths, multiplies the amount of data being handled. In current observability environments, telemetry has to be written, replicated, and buffered multiple times to increase storage and network demand.

Redundancy almost always comes with a cost. Adding more collectors, extra storage copies, or read replicas helps keep the system running when something breaks, but it also means running more infrastructure all the time. Each added layer needs to be deployed, monitored, upgraded. and paid for. Over time, this extra work and spend can creep up quietly, turning reliability improvements into ongoing maintenance and scaling headaches.

These trade-offs usually become visible only after observability has been scaled for production, when reliability improvements quietly translate into sustained cost and operational complexity.

Many teams try to offset these costs with aggressive sampling. By reducing the volume of data ingested, HA becomes more manageable. The trade-off? You lose granularity. The crucial events or minor trends can be overlooked. Observability will begin to decrease unannounced, developing blind spots at the time when you require maximum visibility. A balanced approach between high availability and intelligent controls is essential, but the lesson is clear: being highly available does not come free, and every design choice carries cost and complexity..

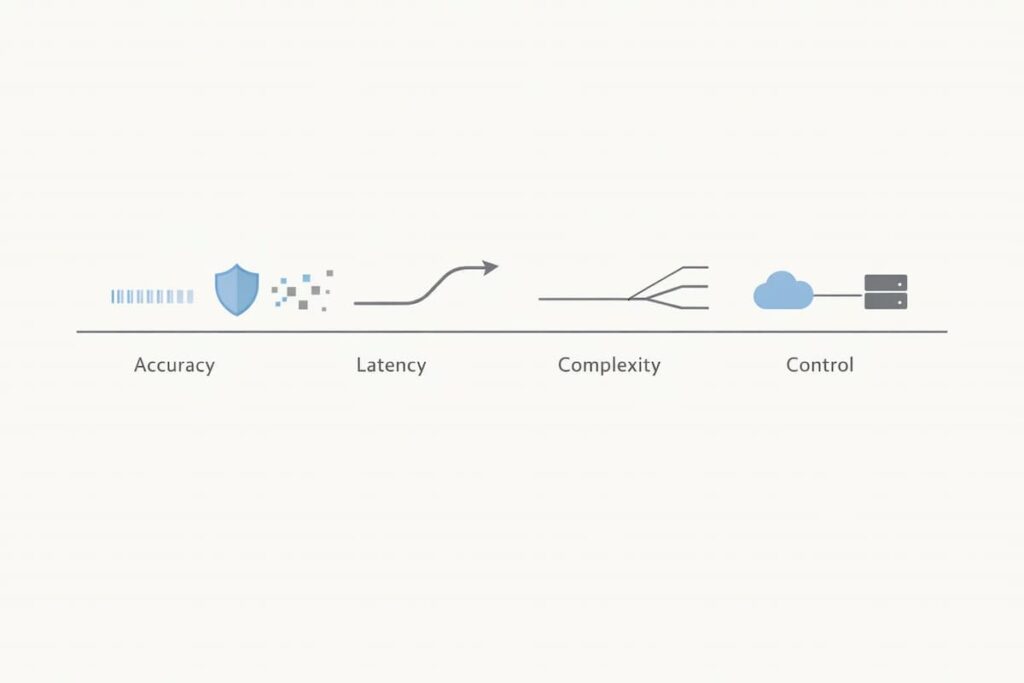

Trade-offs Teams Rarely Consider When Designing HA Observability

Each step towards enhancing an observability system with greater resilience is associated with trade-offs that are typically underestimated by the teams. Realizing these trade-offs prior to designing HA observability can save time, money, and headaches.

- HA vs Data Accuracy: Replication, buffering, or sampling can be used to address spikes and failures in high availability. These methods may corrupt the telemetry data, create gaps or coarse the granularity. The more you prioritize keeping the system online, the more effort you often have to spend making sure metrics, traces, and logs stay accurate.

- HA vs Query Latency: High availability can come at the expense of query speed. When ingestion and query workloads are separated, or when data is replicated across nodes or regions, queries often have to travel further or wait on coordination between systems. The result is dashboards and analytics that feel slower, especially under load, even though the platform is technically “up.”

- HA vs Operational Complexity: To accomplish HA, more moving parts will be added, including many clusters, replicas, pipelines, and monitoring layers. Every additional layer adds configuration overhead, possible points of failure and operational overhead.

- SaaS HA vs In-Infra HA Trade-offs: Using a managed SaaS observability platform may simplify HA by outsourcing infrastructure management, but it limits visibility and control over failure domains. In contrast, self-hosted in-infrastructure HA offers more control but demands higher operational expertise and resources. Neither approach is free from compromises.

High availability is desirable, but it is not free. Every gain in uptime or redundancy comes with costs in accuracy, latency, or complexity.

Failure Handling in Cloud-Native & Kubernetes Environments

Cloud-native and Kubernetes environments enable rapid scaling and deployment, but they also introduce failure patterns that observability systems must be built to handle. Infrastructure is dynamic, services are ephemeral, and dependencies change constantly. Without deliberate failure handling, observability becomes unreliable at the exact moment engineers depend on it most.

Such settings are likely to bring into the limelight two big areas of failure that observability platforms should directly contend with.

Ephemeral Infrastructure Challenges

Telemetry loss is a typical threat caused by short-lived infrastructure.

- Pods restarting: Telemetry streams may also be interrupted by frequent pod restarts and leave gaps unless the data is buffered or retried

- Short-lived services: Short lived services can also generate critical telemetry that is lost prior to being received by the observability backend.

- Lost telemetry: In the absence of local buffering and robust delivery, telemetry of ephemeral components is lost when scaling events or failures occur.

One implementation approach to addressing these challenges is to buffer telemetry close to the source and design delivery paths that tolerate short-lived infrastructure, reducing the risk of permanent visibility gaps during scaling events.

Dependency Explosion

Modern software systems are based on a complicated dependency chain, which increases the effect of failure.

- Third-party APIs: External services may add a latency, error or lost telemetry that the team has no control over.

- Service meshes: Mesh layers provide visibility to the volume and pressure of telemetry in case of an incident.

- Async pipelines: Asynchronous workflows defer signals and complicate the association between cause and effect in a way that is not easily observable.

SaaS vs Self-Hosted Observability: Failure Domains Compared

The decision between SaaS and self-hosted observability lies less in features and more in the locations of failure domains. The move defines the master of infrastructure and the nature in which failures manifest.

Both models have their own risk, and being aware of the risks assists teams in designing observability that remains useful throughout the incidents.

SaaS observability platforms

The provider manages infrastructure and incurs low overheads, but provides opaque failure domains that you cannot directly change. Failures in the provider’s environment, network partitions, or ingestion limits may reduce visibility, leaving you with limited options to either wait or cache data.

Self-hosted observability platforms

Complete management of infrastructure and telemetry routes enables buffering, replication, and scaling on a fine-tuned basis. Any service, queue, or node can be a failure point that teams need to rectify during incidents.

Trade-off between control and responsibility

SaaS leads to simplicity in operations at the expense of control, whereas self-hosted gives more control with operational overhead.

When Observability Becomes the Bottleneck Instead of the Helper

There are moments when observability is pushed far beyond normal conditions. High-traffic incidents, Black Friday-scale peaks, regional outages, and partial cloud failures all create the same problem: telemetry explodes at the exact time engineers need fast answers. When observability systems are not designed for this pressure, they stop helping and start slowing everything down.

This is often the stage where teams begin reassessing their observability platforms and evaluating alternative approaches as reliability, cost, and visibility risks compound at scale.

During peak events, a single service issue can trigger a flood of logs, traces, and metrics across the entire stack. Regional outages and partial cloud failures add network instability and uneven load, making ingestion and queries unpredictable. Many observability platforms respond by failing hard, dropping all data, or becoming unusable just when teams are actively investigating.

This is why observability must degrade gracefully. It is better to have partial data rather than no data. When engineers understand their boundaries, nothing is taken for a chance when it comes to delayed metrics or sampled traces. Robust APM tools are designed to maintain visibility during stress, without preference given to the sudden collapse, but rather controlled degradation, allowing teams to continue onwards, rather than flying blindly.

Designing Observability for Failure: Best Practices

Once you accept that observability will be stressed during incidents, the goal shifts. The question is no longer how to make observability perfect, but how to make it reliable when things break. Systems that assume ideal conditions rarely survive real failures. But those designed for failure do.

Decouple Collection from Storage

Telemetry collection should not depend on storage being healthy. When collection and storage are tightly coupled, any slowdown or outage downstream immediately causes data loss upstream. Decoupling allows collectors to continue accepting data, buffer temporarily, and recover gracefully once storage catches up. This separation gives you time during incidents instead of forcing instant failure.

Plan for Partial Data, Not Perfection

During incidents, complete data is rare. Some signals will arrive late, some will be missing, and some will be sampled. Designing observability to work with partial data is critical. This means making delays, gaps, and sampling visible so engineers understand what they are seeing and what they are not. Partial visibility is far safer than false completeness.

Test Observability Failure Scenarios

Most teams test application failures but never test observability failures. Yet telemetry spikes, network partitions, and ingestion backlogs are predictable under stress. Simulating these scenarios reveals weak points long before a real incident does. If observability only works in calm conditions, it will not work when it matters.

Don’t Rely Solely on Dashboards

Dashboards are useful, but they are not the full picture. During incidents, dashboards can lag, cache data, or hide missing signals. Engineers need access to raw queries, multiple signal types, and system health indicators to validate what they are seeing. Observability works best when dashboards are an entry point, not the final answer.

How Failure Handling Fits Into a Complete Observability Strategy

Failure handling does not live in one tool or one signal. It only works when logs, metrics, traces, and synthetic monitoring are designed to fail together without losing meaning. Each signal answers a different question. Logs explain what happened, metrics show how often and how fast, traces reveal where time was spent, and synthetic monitoring exposes user impact even when internal signals are incomplete.

When failure handling is treated as a feature checkbox, observability breaks under pressure. Synthetic checks can also be passed even when there is actual degradation due to failure of metrics and logs. Here, the team visibility turns out to be a story.

Successful observability also considers failure management as an architectural choice. When ingestion, storage, querying, and alerting are designed to fail together rather than independently, observability degrades more honestly under pressure. This reduces the risk of silent failure modes and helps teams understand what data is delayed, sampled, or missing instead of presenting a misleading sense of health.

Final Thoughts: Observability Must Survive the Incident It’s Meant to Diagnose

Considering that observability is an infrastructure, it remains worth noting that it must survive the incident it debugs. When it fails during incidents, teams lose more than visibility. They lose time, confidence, and the ability to make correct decisions under pressure.

Building reliable observability means assuming failure from the start. Pipelines will overload, networks will partition, and queries will surge at the worst possible moment. Teams that design observability with failure as a first-class assumption are the ones that stay oriented during chaos instead of reacting blindly to partial signals.

Some teams choose in-infrastructure observability to control their failure domains more tightly and avoid external dependencies during outages. The approach matters less than the mindset. Observability must be designed to survive the incident it is meant to diagnose, not become another system that fails when it is needed most.

FAQs

1. Why do observability platforms often fail during major incidents?

Observability platforms are frequently stressed during the same conditions as the systems they monitor—traffic spikes, cascading failures, or infrastructure instability. In these moments, ingestion backpressure, query contention, or control-plane bottlenecks can cause delayed or missing telemetry, even while dashboards appear operational.

2. Does high availability guarantee accurate observability data?

No. High availability ensures components remain reachable, but it does not guarantee data correctness, completeness, or timeliness. Observability systems can remain “up” while silently dropping, delaying, or sampling critical telemetry, leading to misleading signals during incidents.

3. What is the difference between control plane and data plane failures in observability?

Control plane failures affect dashboards, configuration, or UI access, while data plane failures impact telemetry ingestion, storage, and querying. A platform may appear healthy at the control plane level while the data plane is degraded, resulting in partial or outdated visibility.

4. Why can redundancy increase observability cost and complexity?

Redundancy introduces replication, buffering, and coordination overhead across regions and components. While it improves resilience, it also increases infrastructure usage, operational complexity, and cost especially when observability workloads scale rapidly during incidents.

5. How should observability systems degrade during failures?

Effective observability systems should degrade honestly under pressure clearly indicating delayed, sampled, or missing data rather than presenting false confidence. Partial but transparent visibility is more valuable during incidents than complete dashboards built on incomplete data.